Seed catalogs are beginning to arrive in mailboxes and gardeners are beginning to feel the ‘itch’ to order seeds. This week on the farm page, I’ve been sharing tips to help you make the best choices from seed catalog purchases. The tips I am sharing today are kind of all over the place and also there are too many words to fit in a Instagram post, so, I am putting all the nitty gritty in an old fashioned blog post. Let me know if you have any questions I can answer.

The Fine Details

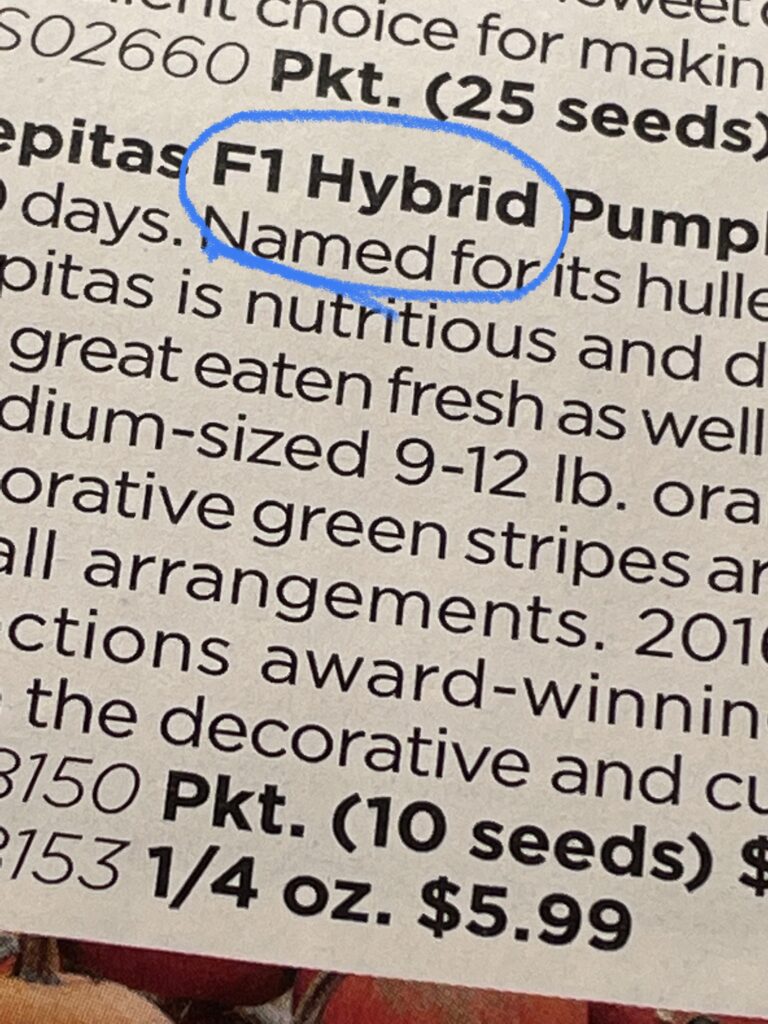

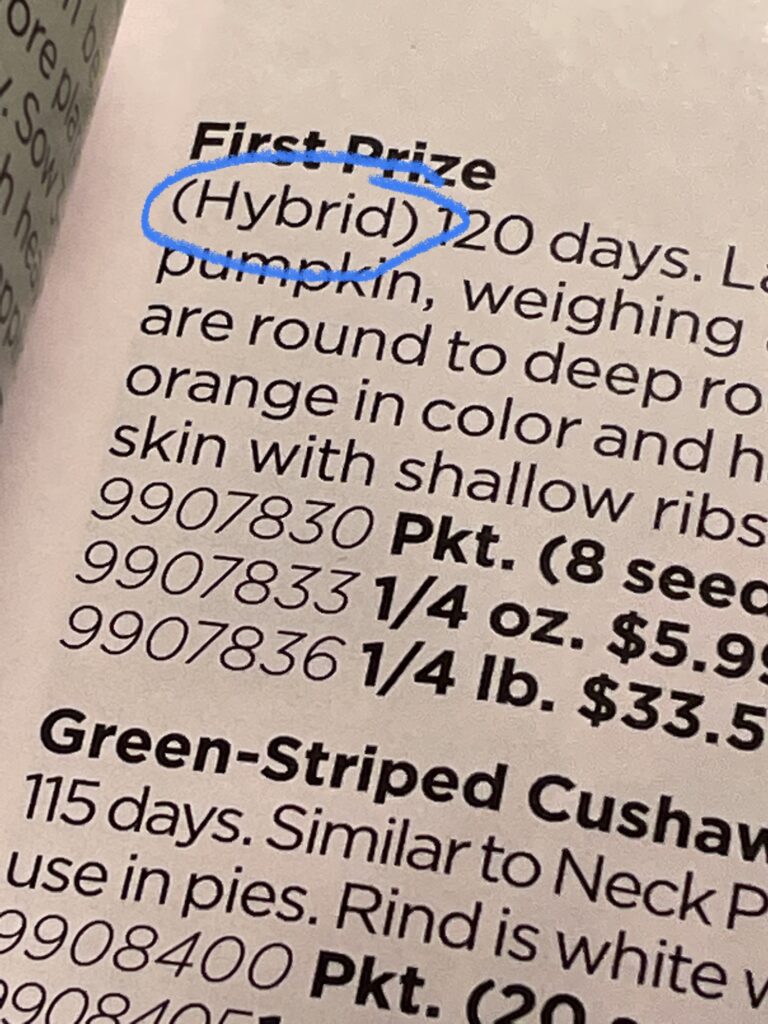

When it’s time to shop for seeds, you will often come across these terms or information in your seed search and it’s helpful to know what they are and how they apply to you:

Hardiness Zone– Seed catalogs may make reference to how well something grows in zone 4, or zones 4-7, or some other number. What hardiness zone are you? Our country is divided into certain growing zones, because certain things grow better in some areas than others. As well, something that grows as a perennial in some zones, may have to be treated as an annual in others. These hardiness zones are based on the average low temperatures during the winter. Something that grows well in Florida may not grow well up here in Michigan due to differences in climate, In the US we start at zone 1, and go up to zone 13. If you were looking in a seed catalog to find a plant that would grow well in your area, knowing your zone will help you pick out the plants that are best suited for you.

When looking at seed catalogs and considering your hardiness zone, sometimes the zones the plant grows well in will be a range, say, zones 3-7. It’s important to make note that if you are trying to grow something in a zone higher than 7, it will not grow well because it needs the dormancy period that winter time provides in those zones. To find your zone, google ‘usda hardiness zone’ with your zip code.

Days to Maturity- This is really useful information especially for those of you with shorter growing seasons. The days to maturity, or days to harvest, is the number of days that you can expect to pass before your first harvest. Harvesting happens over a period of time, it doesn’t all happen in one day, so it’s important to note that days to maturity refers to the point at which you can begin harvesting your vegetables. Of course, weather, soil conditions, etc. can all affect this and the number is not absolute. Also, depending on the seed company that number can refer from the day the seed germinates outdoors in the soil for direct sown plants, but then refer from the day you set your transplants in the ground until harvest, for those seeds you start indoors. Some seed companies use the days to maturity to refer to the day the seed germinates, regardless of where it was sown. There is a huge difference in days to maturity between varieties, so if your growing season is short, you may want to look for a variety with fewer days to maturity to maximize how much you can harvest before your first anticipated frost.

Seed pack size- This is also useful information, especially if you don’t want to end up with 300 broccoli seeds in a packet, or if you were expecting more than 5 seeds in a pack. Every seed packet comes labeled with a weight, and some actually list the minimum number of seeds in a packet. If you use your search engine you can find an approximate number of seeds based on type and weight, and some seed companies specialize in seed packs with smaller quantities especially for gardeners with small gardens. There is no sense in paying for a full packet of seeds when you might find more affordable options with quantities that fit your size better. Of course, if you end up with more seeds than you will use, you can store them from one season to the next, and also have seeds for trading with friends if you wanted.

Last, but not least:

To maximize your purchases, be sure you understand the growing conditions of the plants you will be growing. Perhaps two of the biggest considerations is that of sunlight and drainage. Some plants require full sun in order to produce fruit and grow well. If they don’t have full sun, you may be wasting your money by trying to grow something that is not well suited to your space. The other consideration is drainage, especially for vegetables that grow directly in the soil such as carrots and potatoes. They (and roots of other plants) don’t like to be surrounded by muddy conditions, good drainage is very important. Soil that is not compacted is also important for proper formation and growth of those vegetables that grow in the soil.

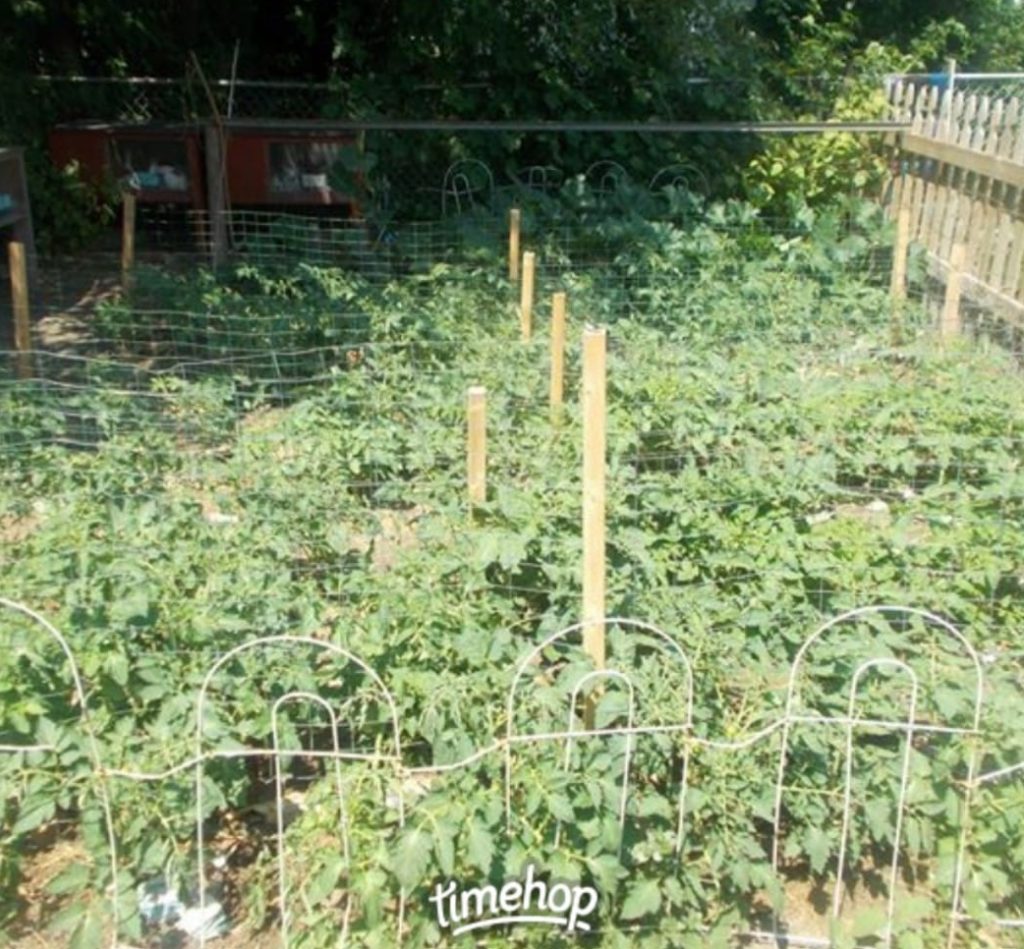

Making a list of what you want to grow, before you open the catalog, is very helpful. This will help keep you centered and –maybe- help you avoid too many impulse splurges that you don’t have room for….. But in all honesty, if your space or budget is limited, make a list of the things that are most important to you. In my early garden days when I had limited space and very limited funds, I’d try to stick with growing the vegetables that would cost us the most to buy, that I had room to grow in my garden. While we’re talking about limited space, don’t forget about growing vertical (trellising, grow bags hanging from fences, etc.), container gardening (squeeze plants in places you otherwise wouldn’t, without breaking ground), and intercropping (planting more than one crop in the same space – but soil health is really important to make this work as is understanding the nutritional needs of your plants and what should be planted next to each other – great time of year right now to research all of this stuff).

As you make your list, simultaneously make a garden map to make sure you have the space to grow the things you want. Space is a very common concern for backyard gardeners because it’s not often unlimited, so growing has to be planned well in order to achieve the most harvest.

As you search catalogs, you may wish to find varieties that will compliment each other with intercropping and not overcrowd – perhaps a variety that will mature quickly and shade the ground of a slower-growing variety that will benefit from the weed suppression, the quicker maturing variety will be harvested and removed before the slower maturing variety, so there will be no competition for space or nutrients. Or, consider succession planting, and when one succession is complete, something else can be planted in its place with enough days to maturity to mature before your last frost. Another consideration would be plants developed especially for container gardening, if you plan to grow in containers. Some varieties of vegetables can be harvested at a ‘baby’ stage and also allowed to mature into a full grown vegetable or leafy green plant, which maximizes your harvest possibilities.

Once your seeds arrive:

I like to check my seeds with my order, then inventory them so I know what variety I purchased, packet weight or how many seeds, how many packets total, and any other notes I think are important.

Occasionally you may find that you have an empty seed packet, or part of your order is missing. Seed companies are happy to fix this right away, so the sooner you let them know, the sooner you will have your whole order. It’s no fun to pack your order away only to notice you’re missing something or you have an empty packet of seeds when you’re ready to start them.

Be sure to store your seeds carefully where they will be cool, dark, and dry.

Also, very important: Just about every seed company that I have ever visited online has a resource section with helpful planting information, charts and even video to help you become a better gardener! Be sure to check them out.